Mystery Internet Bug: Text-to-Speech and The Notorious B.I.G.

Apr 21st, 2022

1788 words (~8 minutes)

I love solving random bugs on the internet! Recently, I’ve gotten more comfortable with browser development tools. Sometimes I’ll be on a website and realize, “Hey, I can open this up and see how it works!” As a result, I’ve had a lot of fun finding bugs on random websites and figuring out why they happen.

This post’s target bug is getting the landing page demo of FPT’s text-to-speech service to play a mashup of Notorious B.I.G’s “Juicy” and the xx’s “VCR”. I’ll walk through all of the steps I took, explaining each the best I can. You shouldn’t need to know Javascript or web technologies to follow along. As long as you know the general ideas of what a web page is (and that Javascript is just the code that handles interactions on a web page) you’ll be good.

How I found the site in the first place

I’ve been teaching myself Vietnamese for a while now, using some combination of Duolingo, the Foreign Service Institute’s Vietnamese Course, and Anki (a digital flash card app). To make flash cards for vocabulary, I need the Vietnamese word, its English translation, and an audio clip of the Vietnamese pronunciation. Getting the audio clip is the harder part; you have to find a good audio source for the sound, open up an audio editor, and clip out individual words. I started using text-to-speech (TTS) apps to avoid that complicated process. Sound of Text (and it’s paid version, Hearling) are useful, but they both use Vietnamese’s northern, or Hanoi, dialect. From what I can tell, in Boston most people speak the southern dialect. Looking for an alternative TTS service led me to FPT.ai, a Vietnamese based software company.

Reproducing the bug

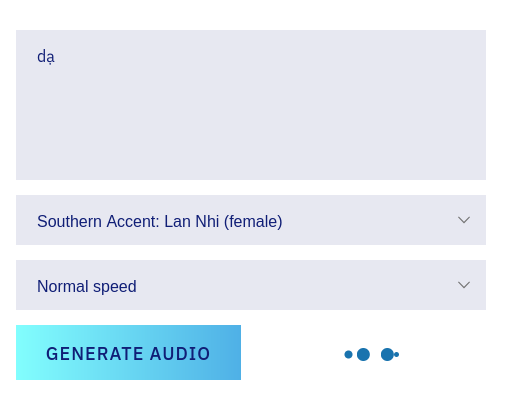

The front page of FPT’s text-to-speech service has a place where you can try it out yourself, and it works fine. If you copy my favorite tongue twister, “Tôi la, ‘Lá lạ là lá độc!’” (I yell, “the strange leaf is the poison leaf!”) into the text area, and click “Generate Audio”, there’s a short loading sound, followed by the text-to-speech audio.

However, we came here to get generate the southern accent. If you select the “Lan Nhi” accent, and type “dạ” (“yes”, one of the words that is pronounced differently between the north and south), the loading sound keeps playing. Then… Biggie starts singing?

This keeps on for the entire song. The lines are from Juicy, but the instrumental is different. Another thing to note is that the loading icon keeps repeating, so we can guess it’s that the text-to-speech service isn’t returning this response.

What specifically hooked me about this weirdness is that FPT’s site seems otherwise well developed. It looks pretty sleek, and the rest of the site works for from what I can tell. So finding what seemed like an easter egg on the product’s front page was surprising.

Mystery 1: Why Biggie?

First thing I always do when something unexpected happens on a website is to go to the dev tools! The keyboard shortcut to get there in either Firefox or Chrome is F12 or Control-Shift-J. There’s a whole lot going on in browser dev tools, but we’re only going to need 3 tabs:

- Console: shows any logs from the webpage, let’s you type Javascript to run

- Debugger (called “Sources” in Chrome): shows you all of the page’s Javascript code

- Network: shows all of the network requests from your browser to the web site.

First, click on the “Console tab”. We’re lucky enough that the most recent console log completely gives away the weirdest part of this mystery.

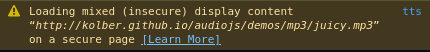

This warning tells us that the audio playing is being served over HTTP, not HTTPS. Decomposing the jargon, HTTP (which stands for HyperText Transfer Protocol) is what the web runs on. Any time you visit a page on a website, your browser uses HTTP to ask the website for that specific page, and the website uses HTTP to send the page back to you. HTTPS uses asymmetric key encryption to keep those pages secret from any one in the middle who might be listening.

This warning happens because the Javascript code on the page is using plain HTTP to download the song, even though the page’s original connection is made using HTTPS.

Back to the main mystery, the console gives us the exact URL of the song: http://kolber.github.io/audiojs/demos/mp3/juicy.mp3.

The root page of that site is just the landing page for audio.js, a Javascript library that plays audio, either using HTML 5 features or Flash apps, back when they were a thing. If we look around the GitHub for the project, we can find that they replaced juicy.mp3 with royalty-free Creative Commons licensed tracks back in 2016. And going even further back, we can find that they removed the juicy.mp3 file from the main project back in 2010. However, the mp3 files stayed on the GitHub pages website, and weren’t updated when the main project replaced everything with the Creative Commons tracks.

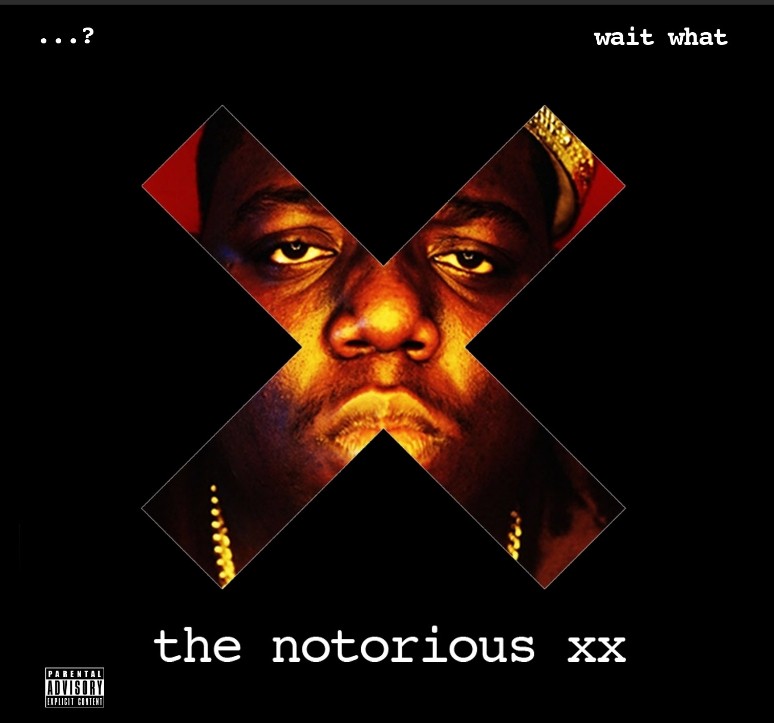

If we download the MP3 itself, we get the MP3’s album cover as well:

The whole album is a mashup of Biggie and the xx by waitwhat, who does all sorts of indie-rock hip-hop mashups. The instrumental is the xx’s VCR. The mash-up is pretty good in my opinion, but it’s probably not the choice I would have made for the demo code of a library.

But we still haven’t answered an important question, where is this mashup even being played? It’s included as a demo in audio.js, but none of the library

code itself is playing it. To answer this, we’d need to be able to search through all of the HTML, Javascript, and CSS code that is downloaded when we visit a webpage. Good thing we can do just that!

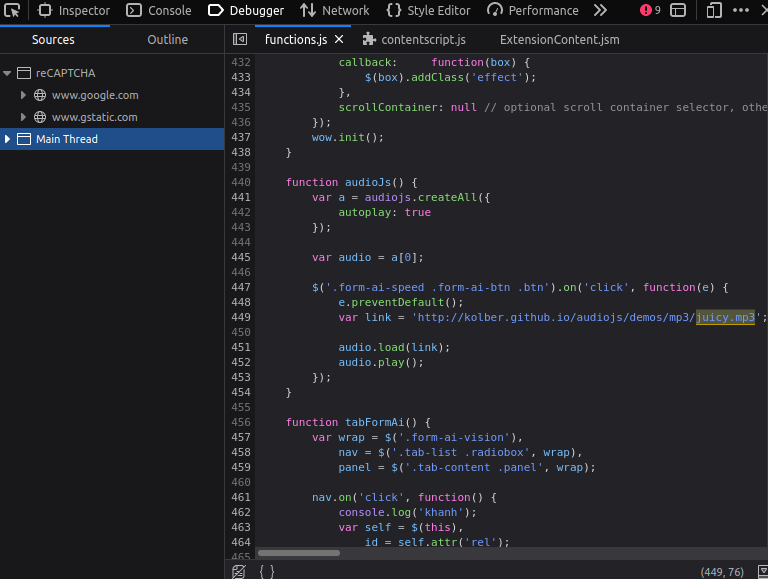

- We can go to the “Debugger” tab (“Sources” in Chrome) of our still-open dev-tools.

- In Firefox, click anywhere in the tab and press Control-Shift-F” to bring up the “find in files” search bar

- in Chrome, you can go to the “Sources” tab, and right click “Top”, then click “Search all files”

- From there, we can search for “juicy.mp3”.

We can see that the functions.js loads the mashup every time someone clicks on button (specifically, any HTML element with the form-ai-speed, form-ai-btn, or btn classes). Mystery solved!

Mystery 2: Why “dạ”

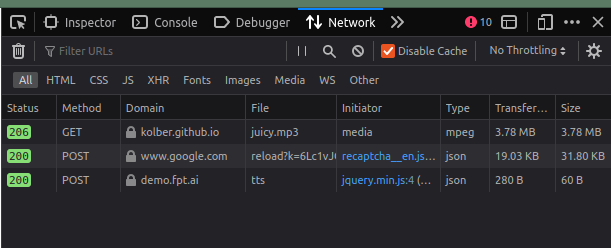

We aren’t quite done yet: why did the input “dạ” trigger the bug, but not anything else? To figure this out, click over to the “Network” tab of the dev tools. This tab lets you look at all of the information going between your browser and the website your visiting (or other sites). When you get to the tab, refresh the page, wait for everything to load, then click the Trash can icon (in Chrome it’s the 🚫 icon) to clear up all of the irrelevant requests. Then, copy “dạ” in, and click “Generate Audio”. You’ll get a few new requests pop up.

.

.

I have an ad blocker on my browser; without it you’ll probably see a few more requests going to tracking sites and Facebook. These are the important ones:

- a GET for the

juicy.mp3that starts playing. From our previous sleuthing that, we know this happens immediately when the button is clicked. - a POST to

www.google.com. We can see that the initiator isrecaptcha__en.js. reCAPTCHA is the “I’m not a robot” checkbox you see on a lot of pages, and in this case is here to make sure that we’re not a bot taking advantage of FPT’s API without making an account first. - a POST to

demo.fpt.ai. This is the one we want to look at! If you click on that line, you’ll see some more info about the request, and if you go to the “Response” tab of the request, you’ll see that there was an error: “Body must have at least 3 characters”. Which explains it: even though “dạ” is a valid word, the API isn’t meant to handle individual words, it’s built for full sentences and longer paragraphs.

Conclusions

There’s not a clear moral of this story. As cool as it is, maybe don’t use unlicensed mashups in your demo projects; it’s caused some legal issues with other projects before and caused them to be copyright-striked until they removed the offending content.

My take-away is that doing detective work like this is fun. I’ve started doing it a lot more since getting comfortable with Javascript and web dev in general. Julia Evans wrote another great post about doing this sort of thing with web APIs.

If you want to dive more into dev tools, you can go to Firefox’s documentation, or Chrome’s documentation.