Credit Across Industries

Jul 14th, 2023

4378 words (~22 minutes)

In 2019, the Event Horizon telescope released the first ever image of a black hole. It was a pretty cool time for science on the internet, but it went awry pretty quickly.

Shortly after the image was released, Katie Bouman, a post doc on the project, posted her reaction to seeing the black hole for the first time to Facebook. The reaction went viral, making Dr. Bouman the de facto face of the project, and highlighting women in STEM in the coolest way possible. But with her fame, came detractors. These detractors had the media literate sense to go past pop-news articles directly to the primary source, the GitHub code repository, but not enough software literacy to understand GitHub’s graph of how many lines of code each person on the project contributed. A particular Reddit post claimed that Katie was taking all of the credit from her co-worker, Andrew Chael, who had committed 800,000 lines of code to the repository. Chael, a grad student at the time, publicly rebutted the idea that he did most of the work, but years later people still go around saying Dr. Bouman did none of the work using misinterpretations of GitHub contributions as their evidence.

When this was happening I remember seeing the issues pretty quickly. Team leads don’t have to write code to have a sizable contribution to a project. And of course no one is actually adding hundreds of thousands of lines of code in only a year or two; Chael himself said most of that was automated code generation. Even on projects I’ve worked on, GitHub thinks that I authored 20 million lines of code, because I added an external dependency in the repository. It wasn’t until much more recently, after watching an incredible documentary focused on figuring out who made the Roblox “OOF” sound effect [footnote 1] that I thought about the situation in more detail. Despite knowing about these issues, I still use GitHub’s contributions tab to discover authorship and credits often. Each commit has an author, or multiple if it’s co-authored. When navigating a repository, it immediately becomes clear who changed what, showing what who’s the expert in each part of the system. It’s tantalizing to take one more step and think that with a little bit of finesse, you have a perfect record of the software’s development and contributions.

It’s a flawed ideal though; only looking at Git misses many contributions needed to make software. What about external dependencies, or stack-overflow answers, or any non-code contribution to a project, like user research, testing, or conversations and ideas? Why does software not seem to have more standards on crediting? What does getting credit even mean, both to community insiders and to the general public? There’s a lot to dive into here, but let’s start this meandering journey with the original corporate-artistic product: the film.

The Film Industry

Films, while being fairly young as an art form, are still the oldest corporate-artistic productions; art that, due to the amount of effort needed to generally produce it, is heavily dependent on the economic models that allow it to exist. Extremely roughly, you can break the film industry’s history into the following timeline:

- The beginning (1900’s)

- Silent films (1910’s - 20’s)

- The studio system (late 1920’s - 1940’s)

- The Auteur and New Hollywood (1950’s - 70’s)

- Blockbusters (1980’s - 1990’s)

- Contemporary (2000’s on)

Focusing on how film makers were credited in each period can tell us a lot. Early films didn’t have many credits at all, at the beginning or the end.

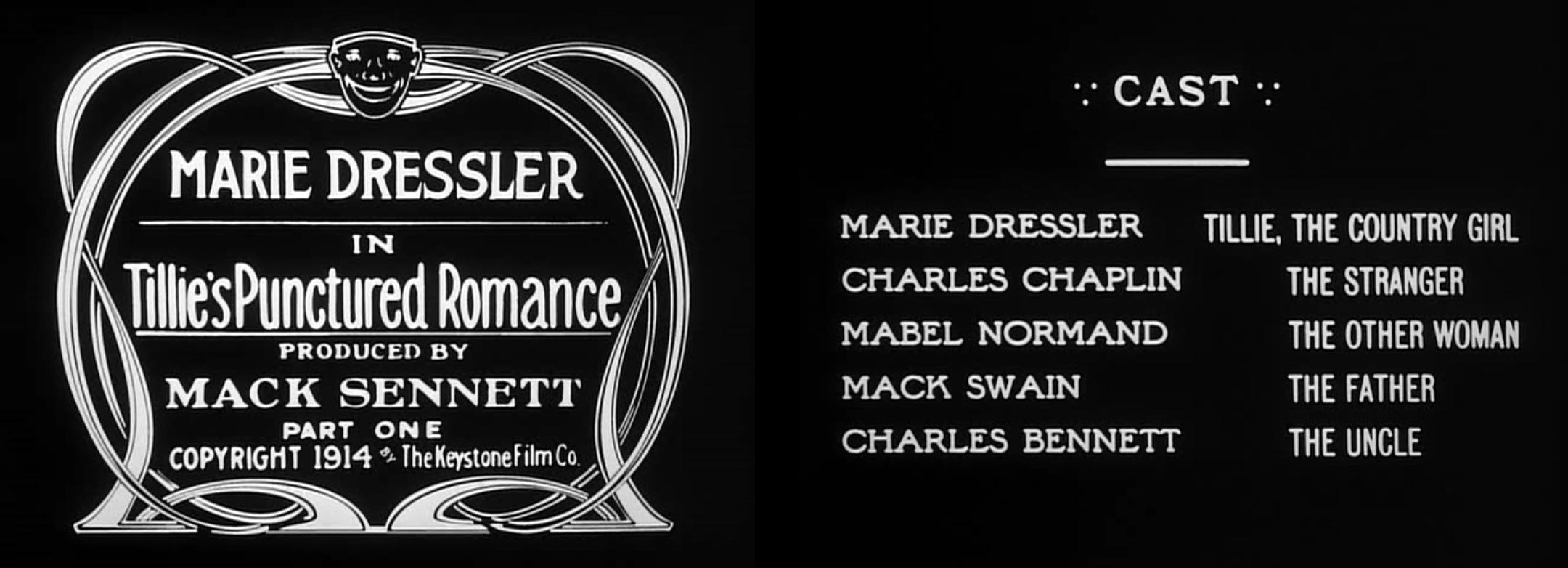

When silent films did start adding credits, they were mostly only for the producers and some of the stars. They usually ran at the beginning of the film, and the producers had final say on who got in the credits.

In the studio system era, the “Big 5” studios not only created the films, but also owned the theaters that showed said films, i.e. a vertical monopoly. In 1948, a Supreme Court decision forced the studios to divest from the theaters, and resulted in the collapse of the studio system.[footnote 2] This led to film makers becoming part of “package units’”, hired on to a film and organized by the producer. So now, studios would only finance and distribute the film, and the creators would work more like free-lancers. With this free-lancing, credit was more important; without a contract with the studio, getting work on new films was easier if you could prove that you had worked on other films. This, in combination with unions getting more power in the 60’s,[footnote 3] and the switch from celluloid to digital have all led to more people getting credit for things they worked on, though producers still have the final say on who gets in the credits.

Despite all of that, it seems that often, film credits still leave out folks who have contributed. Writers specifically seem to get left out often; the Writer’s Guild of America, which arbitrates disagreements on writing credits on films, specifically says that to receive the “Screenplay by” credit, writers “must contribute 50% to the final screenplay” for original works, and need to have contributed “more than 33% of a screenplay” if it’s adapted. They also say “fewer names and fewer types of credit enhance the value of all credits and the dignity of all writers.”

That said, films are different and a bit simpler than software; films (mostly) stop being modified after their release, and they’ve all settled on putting the full credits at the end. Software usually has a much longer lifespan, with no specific “all done” date, and there isn’t an end screen to Microsoft word. However, there’s an intermediate step, where software acts more like films, and has its own complicated history with credits: video games.

The Video Game Industry

Video games have a similar arc to films when looking at who gets credited. Early video game companies didn’t allow employees to put their names on any part of the game. Mark Cerney said that at Atari in the early 80’s, “we were forbidden from telling anyone we worked on the games.” Radio Shack also refused to credit the creators of the TSR-80 games they carried. In the game “Adventure,” Warren Robinett had to completely hide his name in a hidden room in the game, not telling anyone that he had done so.

Japanese companies had similar practices; Namco didn’t (and still doesn’t) allow their staff to be named, and into the late 80’s and early 90’s, Capcom creators credited teams by the team name (i.e. “composition team”), or only gave them pseudonyms shared with other creators at the company. Yoko Shimomura, the composer of most of Street Fighter II, was only credited as “Shimo-P.”, and her picture was only shown if you beat the whole game with a single coin. When those games were ported to home consoles from the arcades, only the arrangers of her music were named in the credits, not Yoko. The sole purpose of refusing to name creators was to give company the upper-hand; it prevented rival game companies from being able to hire away those creators, and gave management the advantage when negotiating.

Video game creators still suffer from poor credits today, with a system considered lagging behind the film industry. In 2008, Rockstar released Manhunt 2, but left out the 55 employees in Rockstar Vienna, who had worked on the game for 2.5 years before being shut down in 2006. Rockstar has also continued to leave out people on their mega titles like GTA 5 and Red Dead Redemption 2. Even this year, 2023, Retro Studios remastered and released Metroid Prime for the Switch, but they didn’t include the credits of the original game. For a remaster, that primarily uses the original code and assets of the games, not crediting the original creators is essentially not crediting the creators who made that game possible.

The International Game Developer Association (IGDA) published a survey in 2006 that said that 35% of the respondents “don’t ever” or “only sometimes” receive credit for things they’ve worked on. In 2014, the IGDA published a crediting guide, but it’s not enforceable without worker unions, so game companies continue to name who they want in the credits, often using them as “motivation” for employees to stay on until launch, in an industry plagued by high turnover.

Software

In my experience, software credits don’t really exist in the same way that video game or film credits do. For example, if I go to the home page for Obsidian, the software I’m using to write this post, I can click around a bit to find their team, but not from the software itself. It’s obvious that this is the current team though, and does not include any past team members.[footnote 4]

Why aren’t software credits as prominent? In contrast to the film and video game industries, software engineers are fairly in demand. Likely, publicly available credits that engineers could use to prove they worked on a product wouldn’t make them more hire-able than they already are. So, company’s don’t look for credits as much, compared to technical interviews or asking for references.

Not all software lacks credits though. It varies from product to product, but the main places I have seen the strongest software credits are in the scientific and open source communities.

Scientific Software

A key differentiator between scientific and general software is publishing and citations. This pushes credits into the economic sphere, as incoming citations are important for early career academics. While more thought is put into making sure that authors are properly credited than most software, authorship on scientific papers[footnote 5] is generally smaller, two to three authors. Authorship is considered a distinct type of contribution, worthy of a slightly higher bar than a simple credit. This is similar to the idea mentioned earlier by the writer’s guild, that crediting fewer people enhances the value of the credit. I’ll try to dissect the difference between authorship and credit in a later section.

When it comes to non-author credits, scientific software has tried a few approaches. Some have tried publishing with large numbers of authors, with some success. From my time in academic spaces though, it hasn’t caught on. To quote Titus Brown, “to nurture a diverse array of valuable scientific contributions, we need new models of publication with new models of authorship.” Some scientists have discussed moving toward a more varied form of credits, closer to the film industry, where tasks completed by different folks are credited differently.[footnote 6]

Open Source Software

Open source also stands out as a software community that prioritizes proper credit. Opening up the “About” window of Firefox and clicking the “global community” link leads to the alphabetic list of contributors. It’s a good page, and they have a documented process on how to be listed on the page.

There are a few differences between this and other types of credits we’ve looked at though:

- There’s no end screen to a piece of software like there is a film or video game. The about page is more difficult to find, and the large majority of people will never look at it.

- Generally open source libraries not related to academia aren’t cited in the same way that scientific software is.

- For Firefox and other open source projects I’ve seen, you have to ask to be listed as a contributor. As with a lot of opt-in things, this is going to be biased towards more confident folks.

I’d say that the thing that makes open source better about credits than general software is the “open” part. At least with older projects, like Linux, that started on mailing lists, most of the contributions to the software were at least discussed on those mailing lists, openly, even if they aren’t explicitly credited in a single place. There are some efforts to address the “all our credits are just Git contributions” problem mentioned in the introduction as well, including allcontributiors.org and corresponding GitHub bot.

Another side of the credit conversation that is active in open source is the legal side, because copyright is the main legal mechanism open source licenses use. There’s a lot out there, primarily distinguishing joint vs individual authorship. But I’m not going to focus on the legal side.

The Philosophy of credits

We’ve gone over the history, and can finally get into the meat of this article; why are credits important?

Oral Histories and Preservation

The only reason I was able to find all that I wrote above is because a historian wrote it down; that by itself is a huge reason to have proper credits. Even decades later, it can be extremely difficult to track down Japanese developers from the 1980’s who made pivotal and iconic games. It’s difficult to interview a developer about the process of making the game if they aren’t listed. Those games are decades old now, and that generation of game developers is aging.

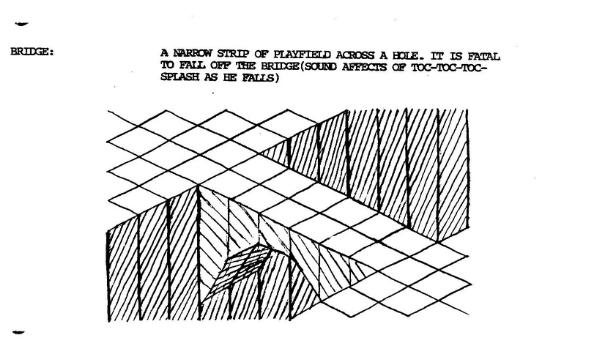

Similarly, the physical resources those developers used are slipping away. Mark Cerney and the other developers of Marble Madness weren’t able to keep their design documents. The only reason they exist today is because an Atari arcade cabinet collector got them from the dumpsters when Atari went out of business.

Even if some historian has already given credit to the proper creators of a work, it takes effort to not let that information slip away again. Our collective knowledge is constantly subject to link rot and other forms of digital degradation. A huge majority of games before 2010 are out of print, leaving photos and videos of game-play as the the only (legal) ways of seeing those game’s credits. The soundtrack for the Terminator Sega CD soundtrack was written by several people, including Tommy Tallarico and Joey Kuras. The game itself only credits Tallarico as the composer though. The album booklet has specific credits for each song, but few people own albums of game soundtracks; most people listen to the re-uploads on YouTube. Re-uploads of songs written by Kuras don’t actually credit Kuras, only Tallarico. Digital degradation affects all media; the historical record of software and video games shouldn’t be written by people who uploaded albums to YouTube in 2011.[footnote 7]

Branding and Independence

The most practical aspect of credits is within the industry itself. As mentioned and hinted at when covering the video game and film industries respectively, preventing people from having individual credits gives their company an upper hand. It weakens employees during negotiation, and makes it less likely other companies will poach them (though not making it less likely that the employee will just leave). In all of these fields, film, games, and applications, companies gain little by crediting creators. Credits dirty the idea of the company as a single entity. The more the public realizes that companies are just a group of people, the more they will realize that those people can and will leave. The Pixar that made Toy Story 2 is not the same Pixar today, and the Valve that made Half-Life 2 doesn’t exist anymore either, because the people who created those works scattered, and are doing great work elsewhere.

Authorship vs Credits

Something I glossed over when covering the film industry is the rise of the Auteur. In the 1960’s, critics started to look at all of the works by a specific director and analyze them in terms of that director’s vision and their vision alone. It’s led to the rise of juggernaut directors like Alfred Hitchcock, Stanley Kubrick, Quinten Tarantino, and Wes Anderson. And while yeah, those directors are skilled, they’re far from the only ones involved in making their films, let alone the only ones who were critical to the film’s vision.

Auteurs are also prominent in the games industry; Sid Meyer, Warren Spector, Hideo Kajima, and Hidetaka Miyazaki are some examples. Game Auteurship is a whole can of worms that I am trying not to open all the way. It is relevant here because in the eyes of the general public, the creation of a game or a film seems to often boil down to a single entity, like the director. Very few people outside of the film or game industry will see or remember detailed credits; credits mostly exist as a fixed record that a creator can refer back to and others can verify. While accurate credits are obviously important, for a game like Elden Ring, many more people will know the name Miyazaki than will know even the co-director of the game, Yui Tanimura, much less lead environment artist Nozomi Shiba.

Huge shout out to Nozomi.

Fame and adoration in the eyes of the general public might not make or break a game creator’s career, but it can definitely be the difference between a successful and a mega-successful career, like in the case of Hideo Kajima, who was forced out of Konami, but was able to make his own game studio and release a successful game, Death Stranding, based on his studio and name alone. In this way, auteurship entrenches those with existing fame, and can give them more leverage to use or abuse their subordinates with.[footnote 8] Software auteurship doesn’t seem to exist in the same way, but certain figureheads do influence projects in similar ways, like Linus Torvalds, the creator of Linux, and Git.

Teamifcation

While not quite the same as auteurship, game studios themselves are generally well known by their output, like From Software, Rockstar, Nintendo, and Valve. Ironically, I’d say that those companies achieved what the film studios of the 1930’s and 40’s desired so much; that people will buy their product, just because the company’s brand is on it.

This is slightly better than auteurship in my opinion; creators are no longer working for a single auteur to realize their auteurship. They are a part of a team, realizing their own vision. It’s just slightly better though, as the idea

- still gives the company leverage to use or abuse employees

- falls apart when looking at the reality of working for big projects. Companies subcontract work on games all the time, and those subcontractors often aren’t credited.

- falls apart when you consider how companies change. Like the ship of Theseus, is a company that’s had 51% of its employees leave since day 1 the same company? What about the game being developed; is it still the company’s game, or does it belong to those 51% employees?

Surprise: both auteurship and teamification reduce to the same thing, someone else getting credit and fame for a successful thing. I haven’t seen alternatives to these two perceptions of companies, where either everyone is treated as one, or one figurehead is pulled out. Only in small indie studios, like Team Cherry, have I seen all team members credited at the same level.

What does any of this mean?

Credits are primarily driven by the realities of their economic models. More credits gives more power to more creators. Credits will initially form if it’s in the creators economic interests, but it won’t be consistent unless it’s enforced by some form of collective bargaining. It’s not the whole story, but it’s a big part.

However, tracking contributions and deciding how to credit everyone in large groups is an inherently hard problem. It’s even harder trying to influence how society views and remembers those contributions. I went into this article thinking that the film industry had it down, but the only thing I’d say that they have are strong unions, who make sure at least some of a film’s contributors have their demands respected.

I have an idea for a project I’d like to create at some point; I’d like to track and show all of the contributions of a common piece of software performing a task, like Firefox on Ubuntu, loading this website, brycewilley.xyz. It would show all of the commit authors of Firefox, as many credits as I can find for the networking libraries, Ubuntu and Linux, DNS, GitHub pages, and the HTML, CSS, and JS standards. That would be impossible to show all at once, but to add to the immensity, I’d try to estimate those uncredited as well; all of the researchers, technical writers, testers, translators, and managers. The sheer number of people who are involved with any given software project is mind-boggling, and it’d be an interesting challenge, at least to show how massive some of the projects in the software industry really are, and to illustrate how much we, in all fields, stand on giants’ shoulders.

Thanks to Kathleen Carroll for the editing help and being a sounding board for these ideas.

-

As mentioned, this video inspired this post, and several of the examples I’ve included came from it’s final chapter. [go back to reference]

-

Interestingly, under the Trump administration in 2018, the Department of Justice announced they “will pursue the termination of outdated judgments around the country”, including the 1948 Supreme Court decision on the film studios. In 2020, Judge Torres granted this termination with a two year sunset, which has presumably passed (though I can’t find anything confirming that), meaning that studios can now own theaters again. [go back to reference]

-

Consider this a “citation needed” note in my own article; I saw the idea that unions directly led to more credits repeated in several different articles, but I couldn’t find any primary sources, like the agreements between the unions and studios. I believe that this idea is true, it just would have been interesting to see the exact mechanisms and agreements about crediting, and when exactly they started to change. Going to put a pin in this for now, since 1960’s Hollywood union contracts are not the main reason I’m writing this post. [go back to reference]

-

Obsidian is a new enough company that it might be all of their developers, but I guarantee you in 5 years there will be turn over, and people will be unlisted from the site. [go back to reference]

-

Not including particle physics, which notoriously has authorship that reaches into the dozens; here’s a random preprint on ArXiv with 77 authors. [go back to reference]

-

All of this is different from who’s legally considered an author. In the scientific software space, that tends to be employers and universities, the legal entities with all the power. [go back to reference]

-

A separate rant: Spotify is simultaneously better and worse at this. Most video game music isn’t on the platform. When it is on there, it’s either covers, or it’s put under a weird artist name. The artist of the Bloodborne soundtrack is “SIE Sound Team” (Sony Interactive Entertainment, but that’s not even clear from the artist page). I’ve been listening to the album for around 10 months, and I only realized when writing this that to see the composer specifically, you have to click through to the credits page. So, it’s good that it’s there, but it doesn’t have details about the recording orchestra or conductor. [go back to reference]

-

Auteurs are also primarily men, and either cements gender bias in the industry (both film and games) or makes it worse. Role models matter. Yoko Shimomura said that “When I joined Capcom originally, the top composers were kind of split into corporate and consumer projects. And both of the top composers were women then. I heard them at the time, and they were talented and made great music. I felt that since the head staff were women, it was easier for other women to join the department.” [go back to reference]